首页 > 医疗资讯/ 正文

[摘要] 乳腺癌术后孤立腋窝淋巴结复发(axillary recurrence,AR)是影响患者预后的关键因素之一。随着诊疗技术的进步,临床对AR的认识逐渐加深,但由于AR发生率较低,目前关于其临床特征的系统性研究仍然有限。ACOSOG Z0011、AMAROS等高质量临床研究证实,在不同前哨淋巴结状态的患者中,腋窝淋巴结清扫(axillary lymph node disp,ALND)与前哨淋巴结切除(sentinel lymph node disp,SLND)在AR控制方面的效果均相当。近年来,腋窝手术去侵袭化的趋势推进了靶向腋窝淋巴结清扫等低创伤手段的诞生。SOUND试验进一步表明,对于肿瘤直径≤2 cm的患者,豁免腋窝手术是安全且可行的。一系列临床研究已识别出了多种潜在的高危因素,包括患者年龄、阳性淋巴结数量、Ki-67增殖指数高、淋巴结外侵犯以及腋窝软组织浸润,然而这些因素与AR的关系并不完全清楚。本综述全面梳理AR的临床特征、高危因素及个体化管理策略,重点探讨不同腋窝手术方式、放疗与系统治疗对AR风险的影响。此外,未来亟待开展更多高质量临床研究,进一步明确AR的预后因素,优化个体化治疗方案,从而为AR患者提供更精准的管理策略。

[关键词] 乳腺癌;区域淋巴结复发;乳腺癌预后

[Abstract] Isolated axillary recurrence (AR) after breast cancer surgery is one of the critical factors influencing patients’ prognosis. With advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques, the clinical understanding of AR has progressively deepened. However, due to the low incidence of AR, systematic studies on its clinical features remain limited. High-quality clinical trials, such as ACOSOG Z0011 and AMAROS, have demonstrated that in patients with varying statuses of sentinel lymph node, axillary lymph node disp (ALND) and sentinel lymph node disp (SLND) provide comparable control of AR. In recent years, the trend towards de-escalation axillary surgery has advanced the development of less invasive techniques such as targeted axillary lymph node disp. The SOUND trial further confirmed the safety and feasibility of omitting axillary surgery in patients with tumors ≤2 cm. In addition, a series of clinical studies have identified a variety of potential high-risk factors, including patient age, number of positive lymph nodes, high Ki-67 proliferation, extranodal extension, and axillary soft tissue infiltration. However, there is no broad consensus regarding the association of these factors with AR. This review comprehensively summarized the clinical characteristics, risk factors and personalized management strategies of AR, with an emphasis on the impact of different axillary surgical approaches, radiotherapy and systemic therapy on the AR risk. In addition, more high-quality clinical studies are urgently needed to further clarify prognostic factors and optimize individualized treatment strategies, so as to provide more precise management for patients.

[Key words] Breast cancer; Regional lymph node recurrence; Breast cancer prognosis

据国际癌症研究机构统计,乳腺癌是2022年全球女性患病率与死亡率最高的恶性肿瘤[1]。随着诊断技术和治疗手段的进步,乳腺癌死亡率在1989年达高峰后持续下降[2],但乳腺癌手术后的复发风险仍是患者面临的严峻问题之一。乳腺癌术后复发转移可分为局部区域复发(locoregional recurrence,LRR)和远处转移复发。远处转移复发是影响乳腺癌患者预后的重要因素,LRR患者发生远处转移的风险较高,复发后的5年总生存率(overall survival,OS)为45%~80%[3]。

局部复发包括同侧乳腺或胸壁,区域复发则涵盖腋窝、锁骨下、锁骨上和内乳淋巴结等。其中,腋窝淋巴结的10年累积复发率为1.3%~5.0%,无论初诊时原发肿瘤是否累及腋窝淋巴结,其复发率均低于其他部位[4]。腋窝淋巴结复发(axillary recurrence,AR)的发生与预后也受患者临床病理学特征及治疗等相关因素的影响,目前仍缺乏针对AR的个性化管理与治疗指南。本综述将总结不同腋窝手术方式对AR发生率的影响、AR相关高危与预后因素,归纳现有治疗方案,并提出未来研究方向。

1 腋窝手术方式对AR的影响

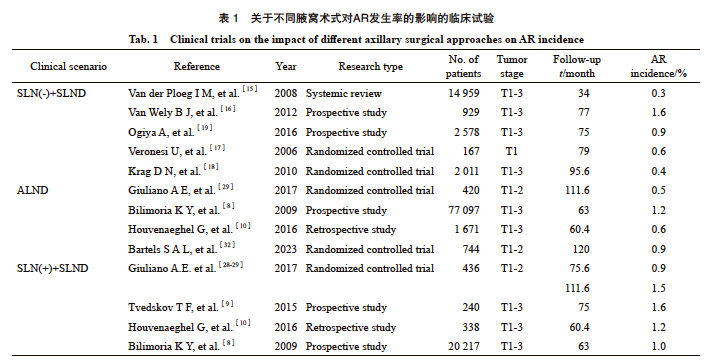

腋窝淋巴结转移是乳腺癌的重要预后因素,是指导局部区域和全身治疗决策的关键。21世纪之前,腋窝淋巴结清扫(axillary lymph node disp,ALND)是乳腺癌腋窝外科管理的标准治疗手段。NSABP B-04研究结果显示,ALND未显著降低腋窝淋巴结阳性患者的区域复发风险(8% vs 11%,P=0.67);而在腋窝淋巴结阴性患者中,ALND的区域复发率显著低于乳房切除术组(4% vs 6%,P=0.002)[5]。多项研究数据证实:未接受腋窝手术的患者AR发生率显著增加(8.9% vs 1.7%,P=0.038)[6];未接受ALND、无LRR的患者的生存率更低[86% vs 71%,风险比(hazard ratio,HR)=2.35,95% CI: 1.91~2.89][7]。有研究[8-13]报道,早期乳腺癌接受ALND后AR的发生率降至2%以下。

1.1 前哨淋巴结(sentinel lymph node,SLN)阴性患者的AR发生率及研究进展

SLN活检的引入开启了乳腺癌外科治疗新时代,也为一部分早期乳腺癌患者提供了豁免ALND的替代方案。目前,SLN无转移的患者仅需接受前哨淋巴结切除(sentinel lymph node disp,SLND)已作为早期乳腺癌的标准治疗手段。毫无疑问,该临床实践是建立在AR发生率极低且患者预后良好的基础之上的[14]。一项纳入14 959例SLN阴性患者的meta分析发现,SLND术后AR发生率仅有0.3%[15]。另一项多中心前瞻性研究[16]表明,SLN阴性患者中出现孤立AR的比例只有1.6%。与之对应的是,多项单中心研究结果显示仅行SLND患者的AR发生率均在0.4%~0.9%[17-22]。虽然以上研究均纳入了一定数量接受术后放疗的患者,但研究[23]显示,即使未接受辅助放疗,进行乳房全切术+SLND的SLN阴性患者在随访16年后的AR发生率仅有1.7%。而多中心SOUND随机对照临床试验[24]则进一步推动了临床淋巴结阴性患者腋窝手术的降级,该临床试验纳入了1 405例肿瘤直径≤2 cm、cN0且术前超声检查无淋巴结受累的患者,经过5.7年随访后研究结果显示,即使SLND组存在13.7%的淋巴结病理学检查结果为阳性的患者,SLND组和无腋窝手术组的5年AR累计发生率差异无统计学意义(0.4% vs 0.4%,P=0.91),初步证实了以上患者省略腋窝手术的安全性。目前针对腋窝管理降级的多中心随机对照研究仍在不断推进,例如BOOG试验[25]和SNIPE试验[26]正进一步探讨低肿瘤负荷患者豁免SLND的可能,有望在SOUND试验的基础上提供更多有力的循证医学证据。

1.2 SLN阳性患者的AR发生率及研究进展

随着乳腺癌放疗及系统性治疗的快速发展,在SLN有限阳性的患者中,不同手术方式(保乳手术、乳房切除术)和腋窝外科管理对AR的影响逐渐受到关注。2016年美国临床肿瘤学会(American Society of Clinical Oncology,ASCO)指南建议,1~2枚SLN转移、接受保乳术联合全乳放疗的早期乳腺癌患者无需接受ALND;SLN转移的乳房切除术后患者应接受ALND[27]。ACOSOG Z0011[11]对1~2枚SLN阳性的保乳手术术后患者开展了研究,所有患者术后均完成了全乳放疗,但未接受任何特异性腋窝治疗。中位随访5年后,SLND组和ALND组的AR发生率相似(0.9% vs 0.5%),差异无统计学意义[28];9.3年的中位随访时间后也得到了相似结论:两组的AR发生率分别仅为1.5%和0.5%(P=0.28)[29]。纳入30项研究的系统综述[30]显示,豁免ALND未对SLN阳性患者的AR发生率及预后造成影响(P=0.69),但能使ALND相关不良事件发生率与LRR发生率(OR=0.76,95% CI: 0.59~0.97)显著降低,另一项meta分析也得到了相同的结论[31]。AMAROS研究[32]显示,对于SLN阳性患者,SLNB联合腋窝Ⅰ~Ⅲ组淋巴结及锁骨上窝内侧放疗与传统ALND在AR控制方面具有相当的效果(1.82% vs 0.93%,表1)。此外,有两项针对腋窝放疗的研究[33-34]进一步支持了这一结论:当放疗野覆盖腋窝Ⅰ~Ⅱ组淋巴结或腋窝Ⅲ级与锁骨上窝时,AR发生率与ALND组差异无统计学意义。同时,IBCSG 23-01[35]等前瞻性或一系列相关的回顾性研究均证实,对于SLN低肿瘤负荷的患者,免除ALND,甚至豁免SLND,仍能将AR发生率控制在1.2%~1.6%这一较低水平[8-10]。除此之外,纳入更多乳房单纯切除手术以及高危患者的SENOMAC临床研究[12]结果显示,在所有患者均接受乳房放疗的情况下,中位随访46.8个月后,SLND和ALND组的区域复发率分别为0.4%、0.5%,远处复发或死亡风险差异无统计学意义。多项前瞻性或回顾性研究[36-39]同样表明,对于1~2枚SLN阳性的乳房切除术后的患者而言,即使未额外接受腋窝放疗, SLND或ALND组的AR发生率或LRR发生率差异无统计学意义。

针对新辅助治疗患者,2024年ASCO指南建议,对于初始腋窝淋巴结阳性的患者,若在新辅助化疗后淋巴结仍有残留病灶,应进行ALND[40]。靶向腋窝淋巴结清扫术(targeted axillary lymph node disp,TAD)的应用能够在减少腋窝手术侵入性的同时,降低淋巴结阳性患者SLND的假阳性率[41]。多项前瞻性与回顾性研究证实,对于新辅助治疗反应较差的患者(ycN+或ypN+)应优先选择TAD联合ALND以确保疗效;而ycN0期患者接受SLND或ALND后的AR发生率均为1%~2%,差异无统计学意义 [42-45]。未来的研究需进一步验证这些策略的长期疗效。

此外,胸大小肌间淋巴结,又称Rotter淋巴结,因其解剖位置的特殊性逐渐受到关注。由于复发率极低,相关研究多为个案报道或早期临床研究,缺乏系统总结。一项纳入了4 097例乳腺癌患者的回顾性研究显示,在接受ALND并中位随访8年的患者中,4例(0.1%)出现Rotter淋巴结复发[46]。值得注意的是,其中3例在初次诊断时腋窝淋巴结状态为阴性。此外,1例侵袭性导管癌伴腋窝淋巴结微转移的患者在术后2年出现Rotter淋巴结复发,尽管已完成术后化疗、内分泌治疗和靶向治疗[47],提示该区域可能作为罕见的复发部位。然而Rotter淋巴结在乳腺癌淋巴引流系统中的病理学特征和临床意义依旧未知总之,腋窝淋巴结转移是患者预后的高危因素[48]。

2 其他可能影响AR的因素

2.1 临床特征

年龄与乳腺癌患者预后的相关性是临床关注的重点之一,但针对AR的研究较少。有研究[4]报道,在不同年龄段中,仅<40岁亚组患者的AR发生率高于5%(5.1%),且多变量竞争风险回归分析也进一步证实了年龄是AR的独立风险因素。另一项前瞻性多中心临床研究[16]结果显示,在SLN阴性患者中,较小的年龄的患者发生AR的风险显著增加(P=0.007),但该研究并未给出年龄的明确界定值。有两项早期研究[45,49]却得出了不同的结论:年龄或绝经状态并非LRR或AR的直接危险因素,肿瘤生物学特点和治疗方案的影响可能更大。此外,不同研究对患者年龄分组的标准存在差异,这种不一致性也可能对研究结论产生一定的影响。

2.2 病理学特征

一般认为,阳性淋巴结数量是与AR直接相关的高危因素。一项纳入13项随机对照临床试验的meta分析评估了8 106例乳房切除术后接受化疗和(或)内分泌治疗的患者中与AR相关的高危因素。中位随访15.2年的结果显示,不同病理学特征患者的10年AR累计发生率差异有统计学意义,从1.3%(T1期、pN0、≥17枚未受累淋巴结)到5%(≥4枚阳性淋巴结、年龄<40岁、0~7枚未受累淋巴结)不等。多变量竞争风险回归分析也显示,阳性淋巴结和未受累淋巴结数量均为AR的关键风险因素。STEPP分析也提示,AR发生率随着未受累淋巴结数量的增加而下降[4]。然而,也有研究[50]对889例SLN阳性和阴性患者的AR发生率开展了研究,结果显示差异无统计学意义(1.2% vs 0.8%)。值得注意的是,该研究所纳入的SLN阳性患者均接受了ALND,因此不能排除腋窝管理方式对SLN阳性患者AR发生率的影响。

与淋巴管血管侵犯相似,淋巴结外侵犯(extracapsular tumor spread,ECS)可能也是AR的高危因素[51-54]。纳入美国得克萨斯大学MD安德森癌症中心5项临床试验的队列研究[55]发现,锁骨上/腋尖淋巴结复发与多个风险因素显著相关:>4枚阳性腋窝淋巴结、>20%腋窝淋巴结受累、淋巴管血管侵犯、存在明显ECS,存在以上高危因素之一的患者10年实际发生率分别为15%、15%、12%和19%(P <0.000 8),而腋下—中淋巴结复发与淋巴结受累数量无显著关联。与淋巴脉管浸润类似,反映淋巴结病灶侵袭程度的ECS也可能是AR的风险因素。一项入组1 475例患者的随机对照临床研究[56]发现,存在腋窝淋巴结ECS的患者10年AR累计发生率更高(4.1% vs 2.1%,P=0.09),但在校正其他风险因素(如淋巴结转移数量)后ECS则不具有独立预测作用。此外,腋窝软组织(axillary soft tissue,AXT)肿瘤细胞浸润通常与阳性淋巴结及ECS并存,也引起了研究者的注意。一项对2 162例淋巴结阳性患者的研究发现,中位随访9.4年后, AXT+ECS组、AXT组、ECS组的10年AR发生率分别为4.5%、4.6%和0.8%(P=0.003 6)。多变量分析提示,AXT与AR(HR=3.3,P=0.003)显著相关,而ECS并未表现出独立影响因素的情况(HR=0.98,P=0.96)[57]。目前推测ECS可能伴随着更多数量的阳性淋巴结(P<0.001),而后者与AR有更强烈的相关性[56]。因此,ECS与AR的关系仍存在争议,未来研究需要在排除其他影响因素后,进一步探究ECS对AR的影响,这将为临床实践提供参考。

针对腋窝淋巴结阴性患者,AR相关风险因素似乎与肿瘤的病理学特征关系更密切。一项中位随访时间为8.3年的研究[58]结果显示,对于接受保乳手术与术后放疗的T1期、SLN阴性患者,Ki-67增殖指数高和组织学类型(导管癌 vs 其他)是AR的独立预后因素。而在纳入2 872例淋巴结阳性的乳腺癌患者的临床研究[59]中,并未发现组织学类型(导管癌 vs 小叶癌)与AR的发生率相关(P=0.20)。另一项针对未接受腋窝手术的老年患者(≥70岁)的研究[6]发现,增殖活跃(Ki-67增殖指数≥20%)和Luminal B型的患者在10年内的AR复发率显著增高,分别达17.1%和16.8%。纳入1 088例单病灶、肿瘤直径≤3 cm患者的随机对照试验则提示,雌激素受体(estrogen receptor,ER)状态、组织学分级、淋巴管血管侵犯、是否接受内分泌治疗均与AR相关(P=0.002, P<0.001,P<0.001,P=0.004)[61]。一项单中心前瞻性临床研究[60]结果显示,在SLN阳性、肿瘤大小≤5 cm、接受SLND与辅助治疗的1 056例cN0患者中,激素受体阴性(P<0.01)、三阴性乳腺癌(P=0.047)、乳房切除术(P<0.01)和未接受辅助放疗(P<0.01)与AR显著相关。一项回顾性研究[21]还发现,SLN阴性患者的核分化程度与AR相关(单因素分析:HR=5.12,95% CI: 1.52~17.26,P<0.01)。不过,这些研究均纳入了特定患者,在一定程度上影响了结论的外推性与适用性。

2.3 治疗特征

放疗是乳腺癌局部治疗的重要组成部分,因此部分研究对放疗与AR的关系进行了探索。有研究[58]表明,对于T1且SLN阴性的乳腺癌患者,部分乳腺照射(partial breast irradiation,PBI)与全乳放疗(whole breast radiotherapy,WBRT)的10年AR累积发生率分别为4.0%和1.3%(P<0.001)。与PBI相比,WBRT能够将AR风险降低约2/3,这为WBRT在预防AR方面的作用提供了相关证据。一项纳入2 767例患者的多中心队列研究[61]显示,与保乳手术加放疗相比,乳房切除术后未加放疗是AR的独立风险因素(HR=2.98,95% CI: 1.44~6.17)。此外,外照射放疗降低SLN阴性患者AR风险的作用也在其他研究中得到了验证,但需考虑所纳入研究的异质性[62-63]。EBCTCG的meta分析[64]表明,乳房切除术后放疗能使腋窝淋巴结阳性患者的LRR发生率显著降低,但研究未单独区分AR的发生率。

腋窝放疗是否能够预防cN0期患者发生AR也是研究者们关心的话题。OTOASOR试验[65]对SLN阳性、T1-2cN0期患者进行了研究,97个月的中位随访时间后,分别接受区域淋巴结放疗和ALND的患者的AR发生率差异无统计学意义(1.7% vs 2.0%,P=1.00)。虽然无病生存率(disease-free survival,DFS)和OS差异无统计学意义,但区域淋巴结放疗组的复发后预后更优(P=0.019 7,HR=0.52)。AMAROS临床试验[32]也得到了相似结论,接受腋窝放疗和ALND的10年累计AR发生率分别为1.82%和0.93%,均表现出极好的区域控制效果。而在年龄≥45岁、肿瘤小于1.2 cm的cN0期患者中,腋窝放疗和未接受腋窝管理的患者AR的发生率均极低(0.5% vs 1.5%),无法进行统计学评估。值得一提的是,在腋窝放疗组中,只有1例患者出现了临床可触及的AR,这提示腋窝放疗可能是低危患者减少AR发生的保护因素[66]。还有研究[57]报道,对于伴有AXT和(或)ECS的淋巴结阳性患者,腋窝放疗剂量<50 Gy可能将AR发生率提高200%(HR=3.0,P=0.04),强调了腋窝放疗在AXT受累人群中的重要性。总之,术后放疗在降低乳腺癌患者AR发生率中扮演着关键角色,然而针对AR的研究多围绕cN0期患者展开,cN1期患者术后是否需要放疗、是否增加区域淋巴结放疗以及放疗与患者术式、淋巴结状态等因素的关系需要更多研究探讨。

另外,一项回顾性系列研究[67]评估了新辅助化疗后腋窝淋巴结阳性状态对AR的影响,结果显示,pN(-)的患者AR发生率显著低于其他pN(+)患者;新辅助治疗后达到病理学完全缓解(pathological complete response,pCR)的cN3b期患者的5年无复发生存率显著提高(HR=0.27,95% CI: 0.07~0.99,P=0.05)[54]。

由于关于AR的研究数量较少,我们还可以借鉴LRR相关的高危因素,如年龄≤45岁[68]或<50岁[51-52,69]、肿瘤大小[69]、阳性淋巴结数量[49]、未受累淋巴结[70]、分子分型[64,71]。然而,考虑到AR的发生机制及其预后与LRR存在差异,因此目前仍需要更多针对AR的独立研究,以便为AR的精准预防、治疗和长期预后评估提供更为有力的依据。

3 腋窝淋巴结区域复发患者预后

虽然腋窝淋巴结在区域淋巴结复发中的发生率相对较低,且预后明显优于锁骨上淋巴结(P<0.000 1)[52,72]或其他区域淋巴结(P=0.004)[73],但有研究[61]发现,AR仍然是无远处转移生存(distant metastasis-free survival,DMFS)、OS及乳腺癌死亡的独立预后因素之一,5年DMFS、OS分别为31.5%~59.2%、 58.0%~59.8%[52],而10年生存期仅2.5年。另外,AR患者的DMFS和OS显著差于其他类型区域淋巴结复发的患者[74]。然而,该研究并未对比分析不同区域复发部位对预后的影响,需要在未来研究中进一步探讨。

一项纳入22例AR患者的单变量分析研究[75]结果显示,诊断原发肿瘤时腋窝淋巴结为阴性、根治性切除复发灶的患者在AR后的生存期更长(5.4年 vs 1.6年,P<0.001)。同样的结论也能在初始ALND术后的59例患者中发现[76-77]。此外,对54例SLN阴性患者进行47个月的随访后的结果表明,原发肿瘤为ER阴性以及接受化疗作为初始治疗的患者OS更低(P=0.012,P=0.021),而不同补救治疗方案、 AR发生时间的早晚与预后无显著关系[78]。

由于AR发生率较低等原因,孤立AR相关临床研究多为观察性研究,且纳入患者数量较少,因此可信区间范围较宽,证据强度较弱,多数研究也无法进行多变量分析。目前关于乳腺癌术后复发的研究多聚焦于LRR,并发现了一系列相关预后因素:年龄<50岁[52]、肿瘤分级 [52,72,79]、腋窝淋巴结状态及数量[52,72,79-80]、原发肿瘤受体状态、[53,72,79,81]是否接受新辅助治疗[72]、DFS或无复发生存率[79-81]、复发时间[52,82]。

然而,由于局部和区域复发的预后差异较大,加上各研究中对LRR的定义不同、各部位所占比例也不同,因此LRR发生率、DMFS、OS等预后指标的范围较为宽泛。有鉴于此,LRR的预后因素并不能完全反映AR的实际情况,我们对AR的生物学行为及其对患者长期预后的影响的了解仍较为有限,亟待更多研究来填补这一空白。

4 AR后的治疗手段

乳腺癌术后AR是高度异质性的疾病,其治疗选择因患者临床表现、肿瘤生物学、复发前接受的治疗、患者意愿以及不同国家医疗实践而异[83],需制定个体化的多模式治疗方案,通常包括手术局部切除复发灶、放疗和系统治疗等3种治疗手段。研究[84-85]显示,与单一治疗方案相比,手术联合放疗(5年OS:63% vs 38.3%,P<0.001)、手术联合系统治疗(5年OS:53.2% vs 35.3%,P=0.02)、手术联合化疗与系统治疗(AR控制率:81.8% vs 36.4%,P=0.005)与较好的预后显著相关。

关于AR的局部手术治疗原则已在全球范围内达成共识。2024年美国国家综合癌症网络(National Comprehensive Cancer Network,NCCN)指南推荐:对于SLNB术后AR的患者,临床首选补救性ALND;而ALND术后复发的患者,则推荐实施复发灶切除±ALND;既往未行术后放疗的AR患者建议补充区域放疗,范围包括患者胸壁、内乳和锁骨上/下淋巴引流区,以提高患者的局部控制率和生存率[86]。《中国乳腺癌术后局部和区域淋巴结复发外科诊治指南(2024版)》[87]也提出了类似的推荐。有研究[84]表明,复发后接受ALND的患者复发灶控制率更优(89% vs 41%,P=0.000 7),但ALND无法预防远处转移的发生(41% vs 65%,P=0.12)。而另一项纳入220例AR患者的研究[85]显示,接受孤立病灶切除术和ALND作为补救性治疗的两组患者的5年DFS、OS差异无统计学意义(P=0.72,P=0.26)。此外,目前有对复发后个性化放射剂量等问题开展了相应研究,美国得克萨斯大学MD安德森癌症中心的159例术后LRR患者被分为标准治疗组(50 Gy+ 10 Gy)和升级治疗组(54 Gy+12 Gy),未观察到两组的5年DFS和OS差异有统计学意义(52% vs 57%,P=0.29;39% vs 43%,P=0.30)[81],这或许能为AR的放疗剂量提供一定参考。

AR是否需要全身治疗是临床关注的重点之一。然而,AR的极低发生率使得关于AR全身治疗方案及其效果的高质量临床研究数据十分有限。CALOR随机对照临床试验[88]可能是目前能够提供参考的唯一高质量研究。该研究纳入了162例LRR患者,其中85例接受术后辅助化疗,从而探究LRR切除后是否加化疗对预后的影响。结果显示,经过中位9年随访时间后,化疗能够显著改善ER阴性患者的10年DFS(70% vs 34%;HR=0.29;95% CI: 0.13~0.67),而ER阳性患者却未能从化疗中获益,化疗组与未化疗组的10年DFS分别为50%和59%。接受化疗对ER阴性患者(73% vs 53%,HR=0.48;95% CI: 0.19~1.2)的10年OS改善程度也优于ER阳性患者(76% vs 66%,HR=0.7;95% CI: 0.32~1.55),但两种干预均无法显著改善OS。另外,交互作用检验证实,化疗的不同疗效主要取决于LRR(而不是原发灶)的ER状态。该研究也从侧面进一步提示,内分泌治疗依旧是ER阳性患者的主要治疗手段。然而该研究的样本量较少,因此无法评估复发灶分子亚型、原发辅助化疗与LRR发生时间以及其他治疗方案(内分泌治疗、靶向药)对LRR患者预后的影响。

5 总结及展望

现阶段,大多数关于AR的研究多为回顾性分析,缺乏前瞻性研究,尤其是大规模、多中心的随机对照试验,使得我们对AR的风险因素、患者预后和最佳治疗策略的认识仍不够全面。因此急需对AR这一患者群体展开更多针对性的临床试验,以迅速建立其治疗标准。

另外,单细胞测序、液体活检等新兴技术的迅速发展,为深入解析AR背后独特的免疫微环境特征、分子机制及特异性治疗靶点提供了有力支持,为精准治疗奠定了理论基础。例如,通过单细胞形态和拓扑分析,研究者对乳腺癌进行了不同生态型的分类,并发现其为无复发生存率的独立预后因素[89]。此外,利用Arc-well测序技术揭示了导管原位癌和复发灶在基因组层面上存在高度相似性,同时携带复发相关的染色体畸变,提示疾病潜在的进化规律[90]。液体活检技术更是为早期复发监测和干预提供了可能,有研究[91-93]表明其在复发前即能检测到循环肿瘤DNA,灵敏度高达89%~93%,并能够提供最长达2年的早期监测窗口期[94]。

通过整合不同肿瘤分型、微环境变化与治疗应答之间的关系,基于临床试验验证分子靶点,将为这部分具备治愈潜力的患者制订个体化治疗方案,进而提高患者的生存率和生活质量。

第一作者:

杜心悦,博士研究生。

通信作者:

柳光宇,主任医师,教授,博士研究生导师,复旦大学附属肿瘤医院乳腺外科副主任。

作者贡献声明:

杜心悦:文献检索及论文写作;邬思雨:论文校对。柳光宇:写作指导与论文审阅。

[参考文献]

[1] BRAY F, LAVERSANNE M, SUNG H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2024, 74(3): 229-263.

[2] GIAQUINTO A N, SUNG H, MILLER K D, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022[J]. CA A Cancer J Clin, 2022, 72(6): 524-541.

[3] AEBI S, GELBER S, ANDERSON S J, et al. Chemotherapy for isolated locoregional recurrence of breast cancer (CALOR): a randomised trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2014, 15(2): 156-163.

[4] KARLSSON P, COLE B F, CHUA B H, et al. Patterns and risk factors for locoregional failures after mastectomy for breast cancer: an International Breast Cancer Study Group report[J]. Ann Oncol, 2012, 23(11): 2852-2858.

[5] FISHER B, MONTAGUE E, REDMOND C, et al. Findings from NSABP Protocol No. B-04-comparison of radical mastectomy with alternative treatments for primary breast cancer. I. Radiation compliance and its relation to treatment outcome[J]. Cancer, 1980, 46(1): 1-13.

[6] CORSO G, MAGNONI F, MONTAGNA G, et al. Long-term outcome and axillary recurrence in elderly women (≥70 years) with breast cancer: 10-years follow-up from a matched cohort study[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2021, 47(7): 1593-1600.

[7] BROMHAM N, SCHMIDT-HANSEN M, ASTIN M, et al. Axillary treatment for operable primary breast cancer[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017, 1(1): CD004561.

[8] BILIMORIA K Y, BENTREM D J, HANSEN N M, et al. Comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy alone and completion axillary lymph node disp for node-positive breast cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2009, 27(18): 2946-2953.

[9] TVEDSKOV T F, JENSEN M B, EJLERTSEN B, et al. Prognostic significance of axillary disp in breast cancer patients with micrometastases or isolated tumor cells in sentinel nodes: a nationwide study[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2015, 153(3): 599-606.

[10] HOUVENAEGHEL G, BOHER J M, REYAL F, et al. Impact of completion axillary lymph node disp in patients with breast cancer and isolated tumour cells or micrometastases in sentinel nodes[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2016, 67: 106-118.

[11] GIULIANO A E, BALLMAN K V, MCCALL L, et al. Effect of axillary disp vs no axillary disp on 10-year overall survival among women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: the ACOSOG Z0011 (alliance) randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2017, 318(10): 918-926.

[12] DE BONIFACE J, TVEDSKOV T F, RYD.N L, et al. Omitting axillary disp in breast cancer with sentinel-node metastases[J]. N Engl J Med, 2024, 390(13): 1163-1175.

[13] LIM S Z, KUSUMAWIDJAJA G, MOHD ISHAK H M, et al. Outcomes of stage Ⅰ and Ⅱ breast cancer with nodal micrometastases treated with mastectomy without axillary therapy[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2021, 189(3): 837-843.

[14] VERONESI U, PAGANELLI G, VIALE G, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary disp in breast cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2003, 349(6): 546-553.

[15] VAN DER PLOEG I C, NIEWEG O E, VAN RIJK M C, et al. Axillary recurrence after a tumour-negative sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and metaanalysis of the literature[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2008, 34(12): 1277-1284.

[16] V A N W E L Y B J , V A N D E N W I L D E N B E R G F J H , GOBARDHAN P, et al. Axillary recurrences after sentinel lymph node biopsy: a multicentre analysis and follow-up of sentinel lymph node negative breast cancer patients [J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2012, 38(10): 925-931.

[17] VERONESI U, PAGANELLI G, VIALE G, et al. Sentinellymph-node biopsy as a staging procedure in breast cancer: update of a randomised controlled study[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2006, 7(12): 983-990.

[18] KRAG D N, ANDERSON S J, JULIAN T B, et al. Sentinellymph- node rep compared with conventional axillarylymph-node disp in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2010, 11(10): 927-933.

[19] OGIYA A, KIMURA K, NAKASHIMA E, et al. Long-term prognoses and outcomes of axillary lymph node recurrence in 2 578 sentinel lymph node-negative patients for whom axillary lymph node disp was omitted: results from one Japanese hospital[J]. Breast Cancer, 2016, 23(2): 318-322.

[20] PEPELS M J, VESTJENS J H M J, DE BOER M, et al. Safety of avoiding routine use of axillary disp in early stage breast cancer: a systematic review[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2011, 125(2): 301-313.

[21] MATSEN C, VILLEGAS K, EATON A, et al. Late axillary recurrence after negative sentinel lymph node biopsy is uncommon[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2016, 23(8): 2456-2461.

[22] MARTELLI G, BARRETTA F, MICELI R, et al. Sentinel node biopsy alone or with axillary disp in breast cancer patients after primary chemotherapy: long-term results of a prospective interventional study[J]. Ann Surg, 2022, 276(5): e544-e552.

[23] CRUZ H S S, VERDIAL F C, SHANNO J N, et al. Axillary recurrence in sentinel lymph node negative mastectomy patients at 16 years median follow up: natural history in the absence of radiation[J]. Clin Breast Cancer, 2025, 25(1): e63-e70.

[24] GENTILINI O D, BOTTERI E, SANGALLI C, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy vs no axillary surgery in patients with small breast cancer and negative results on ultrasonography of axillary lymph nodes: the SOUND randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2023, 9(11): 1557-1564.

[25] VAN ROOZENDAAL L M, VANE M G, VAN DALEN T, et al. Clinically node negative breast cancer patients undergoing breast conserving therapy, sentinel lymph node procedure versus follow-up: a Dutch randomized controlled multicentre trial (BOOG 2013-08)[J]. BMC Cancer, 2017, 17(1): 459.

[26] NADEEM R M. The feasibility of SNIPE trial; sentinel lymph node biopsy vs no-SLNB in patients with early breast cancer[J]. Cancer Res, 2013, 73(24_Supplement): P1-1-26-P1-01-26.

[27] LYMAN G H, TEMIN S, EDGE S B, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2014, 32(13): 1365-1383.

[28] GIULIANO A E, MCCALL L, BEITSCH P, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node disp with or without axillary disp in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 randomized trial[J]. Ann Surg, 2010, 252(3): 426- 432; discussion 432-433.

[29] GIULIANO A E, BALLMAN K, MCCALL L, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node disp with or without axillary disp in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: long-term follow-up from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (alliance) ACOSOG Z0011 randomized trial[J]. Ann Surg, 2016, 264(3): 413-420.

[30] FAN Y J, LI J C, ZHU D M, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison between axillary lymph node disp with no axillary surgery in patients with sentinel node-positive breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMC Surg, 2023, 23(1): 209.

[31] LI C Z, ZHANG P, LV J, et al. Axillary management in patients with clinical node-negative early breast cancer and positive sentinel lymph node: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Front Oncol, 2024, 13: 1320867.

[32] BARTELS S A L, DONKER M, PONCET C, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized controlled EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS trial[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2023, 41(12): 2159-2165.

[33] GAO W Q, LU S S, ZENG Y F, et al. Axilla lymph node disp can be safely omitted in patients with 1-2 positive sentinel nodes receiving mastectomy: a large multi-institutional study and a systemic meta-analysis[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2022, 196(1): 129-141.

[34] ZAVERI S, EVERIDGE S, FITZSULLIVAN E, et al. Extremely low incidence of local-regional recurrences observed among T1-2N1 (1 or 2 positive SLNs) breast cancer patients receiving upfront mastectomy without completion axillary node disp[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2023, 30(12): 7015-7025.

[35] GALIMBERTI V, COLE B F, ZURRIDA S, et al. Axillary disp versus no axillary disp in patients with sentinelnode micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2013, 14(4): 297-305.

[36] SNOW R, REYNA C, JOHNS C, et al. Outcomes with and without axillary node disp for node-positive lumpectomy and mastectomy patients[J]. Am J Surg, 2015, 210(4): 685-693.

[37] FITZSULLIVAN E, BASSETT R L, KUERER H M, et al. Outcomes of sentinel lymph node-positive breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy without axillary therapy[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2017, 24(3): 652-659.

[38] JOO J H, KIM S S, SON B H, et al. Axillary lymph node disp does not improve post-mastectomy overall or disease-free survival among breast cancer patients with 1-3 positive nodes[J]. Cancer Res Treat, 2019, 51(3): 1011-1021.

[39] TINTERRI C, CANAVESE G, GATZEMEIER W, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy versus axillary lymph node disp in breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy with one to two metastatic sentinel lymph nodes: sub-analysis of the SINODAR-ONE multicentre randomized clinical trial and reopening of enrolment[J]. Br J Surg, 2023, 110(9): 1143-1152.

[40] WEBER W P, HANSON S E, WONG D E, et al. Personalizing locoregional therapy in patients with breast cancer in 2024: tailoring axillary surgery, escalating lymphatic surgery, and implementing evidence-based hypofractionated radiotherapy[J]. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 2024, 44(3): e438776.

[41] CAUDLE A S, YANG W T, KRISHNAMURTHY S, et al. Improved axillary evaluation following neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer using selective evaluation of clipped nodes: implementation of targeted axillary disp[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2016, 34(10): 1072-1078.

[42] PILTIN M A, HOSKIN T L, DAY C N, et al. Oncologic outcomes of sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2020, 27(12): 4795-4801.

[43] WONG S M, BASIK M, FLORIANOVA L, et al. Oncologic safety of sentinel lymph node biopsy alone after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2021, 28(5): 2621-2629.

[44] KUEMMEL S, HEIL J, BRUZAS S, et al. Safety of targeted axillary disp after neoadjuvant therapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer[J]. JAMA Surg, 2023, 158(8): 807-815.

[45] MONTAGNA G, MRDUTT M M, SUN S X, et al. Omission of axillary disp following nodal downstaging with neoadjuvant chemotherapy[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2024, 10(6): 793-798.

[46] KOMENAKA I K, BAUER V P, SCHNABEL F R, et al. Interpectoral nodes as the initial site of recurrence in breast cancer[J]. Arch Surg, 2004, 139(2): 175-178.

[47] HANSEN S M, HOYER U. A case of locoregional recurrence of breast cancer in the interpectoral lymph nodes: an unusual location[J]. Ann Breast Surg, 2019, 3: 6.

[48] JATOI I, HILSENBECK S G, CLARK G M, et al. Significance of axillary lymph node metastasis in primary breast cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 1999, 17(8): 2334-2340.

[49] TAGHIAN A, JEONG J H, MAMOUNAS E, et al. Patterns of locoregional failure in patients with operable breast cancer treated by mastectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy with or without tamoxifen and without radiotherapy: results from five National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project randomized clinical trials[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2004, 22(21): 4247-4254.

[50] GARC.A FERN.NDEZ A, CHABRERA C, GARC.A FONT M, et al. Positive versus negative sentinel nodes in early breast cancer patients: axillary or loco-regional relapse and survival. A study spanning 2000-2012[J]. Breast, 2013, 22(5): 902-907.

[51] CHEN X X, YU X L, CHEN J Y, et al. Analysis in early stage triple-negative breast cancer treated with mastectomy without adjuvant radiotherapy: patterns of failure and prognostic factors[J]. Cancer, 2013, 119(13): 2366-2374.

[52] WAPNIR I L, ANDERSON S J, MAMOUNAS E P, et al. Prognosis after ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and locoregional recurrences in five National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project node-positive adjuvant breast cancer trials[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2006, 24(13): 2028-2037.

[53] GALIMBERTI V, MANIKA A, MAISONNEUVE P, et al. Longterm follow-up of 5 262 breast cancer patients with negative sentinel node and no axillary disp confirms low rate of axillary disease[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2014, 40(10): 1203-1208.

[54] ANDRING L M, DIAO K, SUN S, et al. Locoregional management and prognostic factors in breast cancer with ipsilateral internal mammary and axillary lymph node involvement[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2022, 113(3): 552-560.

[55] STROM E A, WOODWARD W A, KATZ A, et al. Clinical investigation: regional nodal failure patterns in breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy without radiotherapy[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2005, 63(5): 1508-1513.

[56] GRUBER G, COLE B F, CASTIGLIONE-GERTSCH M, et al. Extracapsular tumor spread and the risk of local, axillary and supraclavicular recurrence in node-positive, premenopausal patients with breast cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2008, 19(8): 1393-1401.

[57] NAOUM G E, OLADERU O, ABABNEH H, et al. Pathologic exploration of the axillary soft tissue microenvironment and its impact on axillary management and breast cancer outcomes[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2024, 42(2): 157-169.

[58] GENTILINI O, BOTTERI E, LEONARDI M C, et al. Ipsilateral axillary recurrence after breast conservative surgery: the protective effect of whole breast radiotherapy[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2017, 122(1): 37-44.

[59] MAGNONI F, CORSO G, MAISONNEUVE P, et al. Comparison of long-term outcome between clinically high risk lobular versus ductal breast cancer: a propensity score matched study[J]. EClinicalMedicine, 2024, 71: 102552.

[60] SEKINE C, NAKANO S, MIBU A, et al. Breast cancer hormone receptor negativity, triple-negative type, mastectomy and not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy were associated with axillary recurrence after sentinel lymph node biopsy[J]. Asian J Surg, 2020, 43(1): 148-153.

[61] CAMPBELL I, WETZIG N, UNG O, et al. 10-year axillary recurrence in the RACS SNAC1 randomised trial of sentinel lymph node-based management versus routine axillary lymph node disp[J]. Breast, 2023, 70: 70-75.

[62] DE BONIFACE J, FRISELL J, BERGKVIST L, et al. Breastconserving surgery followed by whole-breast irradiation offers survival benefits over mastectomy without irradiation[J]. Br J Surg, 2018, 105(12): 1607-1614.

[63] VAN WELY B J, TEERENSTRA S, SCHINAGL D X, et al. Systematic review of the effect of external beam radiation therapy to the breast on axillary recurrence after negative sentinel lymph node biopsy[J]. Br J Surg, 2011, 98(3): 326-333.

[64] CHEUN J H, KIM H K, MOON H G, et al. Locoregional recurrence patterns in patients with different molecular subtypes of breast cancer[J]. JAMA Surg, 2023, 158(8): 841-852.

[65] S.VOLT ., P.LEY G, POLG.R C, et al. Eight-year follow up result of the OTOASOR trial: the optimal treatment of the axilla-surgery or radiotherapy after positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer: a randomized, single centre, phase Ⅲ, non-inferiority trial[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol EJSO, 2017, 43(4): 672-679.

[66] VERONESI U, ORECCHIA R, ZURRIDA S, et al. Avoiding axillary disp in breast cancer surgery: a randomized trial to assess the role of axillary radiotherapy[J]. Ann Oncol, 2005, 16(3): 383-388.

[67] LEE S B, KIM H, KIM J, et al. Prognosis according to clinical and pathologic lymph node status in breast cancer patients who underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy alone after neoadjuvant therapy[J]. PLoS One, 2021, 16(5): e0251597.

[68] ZHAO X R, TANG Y, WANG S L, et al. Locoregional recurrence patterns in women with breast cancer who have not undergone post-mastectomy radiotherapy[J]. Radiat Oncol, 2020, 15(1): 212.

[69] ABI-RAAD R, BOUTRUS R, WANG R, et al. Patterns and risk factors of locoregional recurrence in T1-T2 node negative breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy: implications for postmastectomy radiotherapy[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011, 81(3): e151-7.

[70] KARLSSON P, COLE B F, PRICE K N, et al. The role of the number of uninvolved lymph nodes in predicting locoregional recurrence in breast cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2007, 25(15): 2019-2026.

[71] VANE M L G, MOOSSDORFF M, VAN MAAREN M C, et al. Conditional regional recurrence risk: the effect of event-free years in different subtypes of breast cancer[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2021, 47(6): 1292-1298.

[72] WU H L, LU Y J, LI J W, et al. Prior local or systemic treatment: a predictive model could guide clinical decision-making for locoregional recurrent breast cancer[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 11: 791995.

[73] HARRIS E E R, HWANG W T, SEYEDNEJAD F, et al. Prognosis after regional lymph node recurrence in patients with stage Ⅰ-Ⅱ breast carcinoma treated with breast conservation therapy[J]. Cancer, 2003, 98(10): 2144-2151.

[74] SEKI H, OGIYA A, NAGURA N, et al. Prognosis of isolated locoregional recurrence after early breast cancer with immediate breast reconstruction surgery: a retrospective multi-institutional study[J]. Breast Cancer, 2024, 31(5): 935-944.

[75] DE BOER R, HILLEN H F, ROUMEN R M, et al. Detection, treatment and outcome of axillary recurrence after axillary clearance for invasive breast cancer[J]. Br J Surg, 2001, 88(1): 118-122.

[76] VOOGD A C, CRANENBROEK S, DE BOER R, et al. Longterm prognosis of patients with axillary recurrence after axillary disp for invasive breast cancer[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol EJSO, 2005, 31(5): 485-489.

[77] FREDRIKSSON I, LILJEGREN G, ARNESSON L G, et al. Consequences of axillary recurrence after conservative breast surgery[J]. Br J Surg, 2002, 89(7): 902-908.

[78] BULTE J P, VAN WELY B J, KASPER S, et al. Long-term follow-up of axillary recurrences after negative sentinel lymph node biopsy: effect on prognosis and survival[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2013, 140(1): 143-149.

[79] KUO S H, HUANG C S, KUO W H, et al. Comprehensive locoregional treatment and systemic therapy for postmastectomy isolated locoregional recurrence[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2008, 72(5): 1456-1464.

[80] LEE Y J, PARK H, KANG C M, et al. Risk stratification system for groups with a low, intermediate, and high risk of subsequent distant metastasis and death following isolated locoregional recurrence of breast cancer[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2020, 179(2): 315-324.

[81] SKINNER H D, STROM E A, MOTWANI S B, et al. Radiation dose escalation for loco-regional recurrence of breast cancer after mastectomy[J]. Radiat Oncol, 2013, 8: 13.

[82] PEDERSEN R N, MELLEMKJ.R L, EJLERTSEN B, et al. Mortality after late breast cancer recurrence in Denmark[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2022, 40(13): 1450-1463.

[83] MORGAN J L, CHENG V, BARRY P A, et al. The MARECA (national study of management of breast cancer locoregional recurrence and oncological outcomes) study: national practice questionnaire of United Kingdom multi disciplinary decision making[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2022, 48(7): 1510-1519.

[84] NEWMAN L A, HUNT K K, BUCHHOLZ T, et al. Presentation, management and outcome of axillary recurrence from breast cancer[J]. Am J Surg, 2000, 180(4): 252-256.

[85] KONKIN D E, TYLDESLEY S, KENNECKE H, et al. Management and outcomes of isolated axillary node recurrence in breast cancer[J]. Arch Surg, 2006, 141(9): 867-872; discussion 872-874.

[86] National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology, 2024[EB/OL]. Breast cancer (version 4.2024). (2024-07-03)[2024-8-24]. https://www.nccn.org/.

[87] 郝晓鹏, 陈玉辉, 王建东. 中国乳腺癌术后局部和区域淋巴结复发外科诊治指南(2024版)[J]. 中国实用外科杂志, 2024, 44(2): 134-138.

HAO X P, CHEN Y H, WANG J D. Chinese guidelines for surgical diagnosis and treatment of local and regional lymph node recurrence after breast cancer surgery(2024 edition)[J]. Chin J Pract Surg, 2024, 44(2): 134-138.

[88] WAPNIR I L, PRICE K N, ANDERSON S J, et al. Efficacy of chemotherapy for ER-negative and ER-positive isolated locoregional recurrence of breast cancer: final analysis of the CALOR trial[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2018, 36(11): 1073-1079.

[89] ZHAO S, CHEN D P, FU T, et al. Single-cell morphological and topological atlas reveals the ecosystem diversity of human breast cancer[J]. Nat Commun, 2023, 14(1): 6796.

[90] WANG K L, KUMAR T, WANG J K, et al. Archival single-cell genomics reveals persistent subclones during DCIS progression[J]. Cell, 2023, 186(18): 3968-3982.e15.

[91] COOMBES R C, PAGE K R, SALARI R, et al. Personalized detection of circulating tumor DNA antedates breast cancer metastatic recurrence[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 25(14): 4255-4263.

[92] OLSSON E, WINTER C, GEORGE A, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA in patients with primary breast cancer for detection of occult metastatic disease[J]. EMBO Mol Med, 2015, 7(8): 1034-1047.

[93] BIDARD F C, HARDY-BESSARD A C, DALENC F, et al. Switch to fulvestrant and palbociclib versus no switch in advanced breast cancer with rising ESR1 mutation during aromatase inhibitor and palbociclib therapy (PADA-1): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2022, 23(11): 1367-1377.

[94] PAPAKONSTANTINOU A, GONZALEZ N S, PIMENTEL I, et al. Prognostic value of ctDNA detection in patients with early breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Cancer Treat Rev, 2022, 104: 102362.

- 搜索

-

- 1000℃李寰:先心病肺动脉高压能根治吗?

- 1000℃除了吃药,骨质疏松还能如何治疗?

- 1000℃抱孩子谁不会呢?保护脊柱的抱孩子姿势了解一下

- 1000℃妇科检查有哪些项目?

- 1000℃妇科检查前应做哪些准备?

- 1000℃女性莫名烦躁—不好惹的黄体期

- 1000℃会影响患者智力的癫痫病

- 1000℃治女性盆腔炎的费用是多少?

- 标签列表

-

- 星座 (702)

- 孩子 (526)

- 恋爱 (505)

- 婴儿车 (390)

- 宝宝 (328)

- 狮子座 (313)

- 金牛座 (313)

- 摩羯座 (302)

- 白羊座 (301)

- 天蝎座 (294)

- 巨蟹座 (289)

- 双子座 (289)

- 处女座 (285)

- 天秤座 (276)

- 双鱼座 (268)

- 婴儿 (265)

- 水瓶座 (260)

- 射手座 (239)

- 不完美妈妈 (173)

- 跳槽那些事儿 (168)

- baby (140)

- 女婴 (132)

- 生肖 (129)

- 女儿 (129)

- 民警 (127)

- 狮子 (105)

- NBA (101)

- 家长 (97)

- 怀孕 (95)

- 儿童 (93)

- 交警 (89)

- 孕妇 (77)

- 儿子 (75)

- Angelababy (74)

- 父母 (74)

- 幼儿园 (73)

- 医院 (69)

- 童车 (66)

- 女子 (60)

- 郑州 (58)