首页 > 医疗资讯/ 正文

2020年癌症统计报告显示,全球新增确诊癌症病例约1929万,癌症死亡病例约996万,其中我国癌症死亡人数约300万,位居全球第一[1]。近20年来,抗肿瘤药物发展迅速,从化疗药物到各类新型抗肿瘤药物,包括分子靶向药物和免疫治疗药物层出不穷,然而抗肿瘤药物响应率仍然有限,获得性耐药频发及不良反应问题严重限制了其临床应用[2]。

随着高通量测序和其他“组学”的发展,“药物微生物组学”概念兴起[3],同时越来越多的研究表明人体微生物菌群,特别是肠道菌群在抗肿瘤药物疗效中发挥重要作用[4]。本文就微生物菌群与化疗药物、分子靶向药物、免疫治疗药物的疗效及不良反应相关性研究进行综述,以期为临床抗肿瘤药物个体化治疗提供参考。

1 微生物菌群对化疗药物疗效及不良反应的影响

根据微生物菌群调节化疗药物疗效的机制,Alexander等将其调节作用归纳为菌群转运(translocation)、免疫调节(immunomodulation)、菌群代谢物(metabolism)、药物代谢酶(enzymatic)及菌群多样性降低(reduced diversity),即“TIMER”框架[5]。

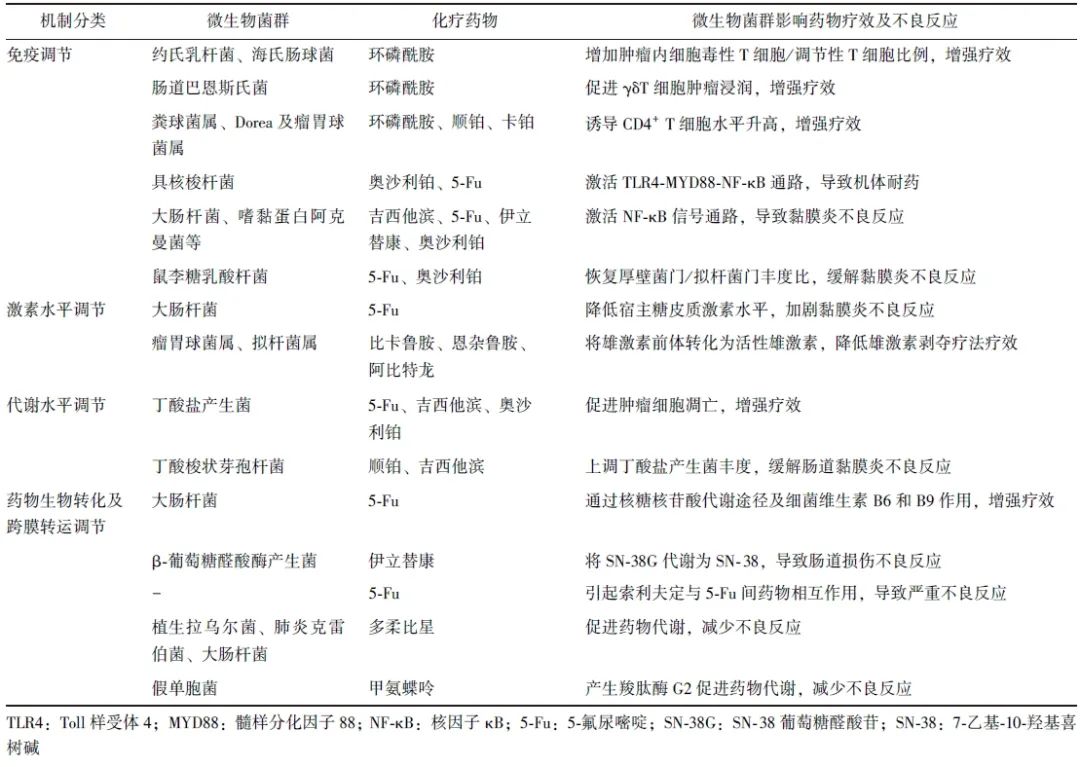

微生物菌群与化疗药物相互作用机制亦可概括为免疫调节、激素水平调节、代谢物水平调节、药物生物转化及跨膜转运调节(表1)。

表1 微生物菌群对化疗药物疗效及不良反应的影响及其作用机制

1.1 调节机体免疫应答影响化疗药物疗效及不良反应

2013年,Viaud及Iida提出肠道微生物菌群通过调节宿主免疫系统,影响抗肿瘤药物疗效[6-7]。研究发现,环磷酰胺可促进部分肠道革兰阳性菌(约氏乳杆菌、海氏肠球菌)向次级淋巴器官转移,增加肿瘤内细胞毒性T细胞/调节性T细胞比例,同时革兰阴性杆菌肠道巴恩斯氏菌可促进γδT细胞肿瘤浸润,从而增强环磷酰胺疗效[7-8]。Li等[9]也发现肠道菌群如粪球菌属、Dorea及瘤胃球菌属可引起乳腺癌患者外周血及肿瘤组织中CD4+ T细胞水平升高,从而增强环磷酰胺、顺铂、卡铂药物疗效。

微生物菌群可通过调节机体固有免疫参与化疗药物耐药途径,导致药物疗效降低。Toll样受体(TLR)4- 髓样分化因子88(MYD88)- 核因子κB(NF-κB)是具核梭杆菌感染的固有免疫信号通路,该通路激活可促进自噬相关蛋白表达,上调凋亡抑制蛋白BIRC3(BIRC3),导致结直肠癌(CRC)患者对奥沙利铂及5-氟尿嘧啶(5-Fu)产生耐药性[10-11],提示肿瘤组织中具核梭杆菌丰度可能是预测5-Fu耐药及患者预后的方法之一。

微生物菌群激活机体固有免疫不仅参与化疗药物耐药途径,还与化疗药物诱导的黏膜炎不良反应相关。固有免疫细胞表达的TLR及NOD样受体识别病原体相关模式分子可进一步激活NF-κB信号通路,导致肿瘤坏死因子-α(TNF-α)、白细胞介素(IL)-1β和IL-6上调引起黏膜损伤[12]。

多柔比星引起细菌内毒素水平升高,吉西他滨诱导肠道中大肠杆菌及嗜黏蛋白阿克曼菌丰度上升,5-Fu、伊立替康、奥沙利铂也可导致肠道菌群紊乱,涉及双歧杆菌属、嗜黏蛋白阿克曼菌等13个菌属,从而激活NF-κB信号通路导致肠道损伤不良反应[13-15]。

1.2 调节机体激素水平影响化疗药物不良反应

研究显示,接受雄激素轴靶向治疗(比卡鲁胺、恩杂鲁胺或阿比特龙)的前列腺癌患者肠道中,能够进行类固醇激素生物合成的细菌丰度更高[16],Pernigoni等[17]也证实与激素敏感性前列腺癌患者相比,去势抵抗性前列腺癌患者肠道中瘤胃球菌属及拟杆菌属丰度较高,其可将雄激素前体转化为活性雄激素,降低雄激素剥夺疗法的疗效。

糖皮质激素通过促进膜联蛋白-1、IL-10的合成等发挥抗炎作用[18],而研究发现小鼠肠道中大肠杆菌可降低宿主糖皮质激素水平,阻断糖皮质激素受体,加剧5-Fu化疗诱导的黏膜炎[19]。

1.3 调节机体代谢水平影响化疗药物疗效及不良反应

肠道菌群可代谢产生短链脂肪酸,包括乙酸盐、丙酸盐和丁酸盐等,其中丁酸盐具有抗炎、调节黏膜免疫/微生物群落及抑制多种致癌信号通路等功能[20]。在抗癌活性方面,丁酸盐联合5-Fu、吉西他滨、奥沙利铂,通过抑制G蛋白偶联受体109a-蛋白激酶B信号通路、促进IL-12诱导的CD8+ T细胞活化通路等机制,促进肿瘤细胞凋亡、降低小鼠肿瘤负荷。同时,与对奥沙利铂无应答的肿瘤患者相比,应答者血浆丁酸盐水平更高,提示丁酸盐可增强化疗药物药效[21-23]。

在缓解化疗药物不良反应方面,丁酸梭状芽孢杆菌可促进双歧杆菌、瘤胃球菌科和颤杆菌克属等丁酸盐产生菌丰度增加,提高小鼠肠道中丁酸盐水平,缓解顺铂及吉西他滨所致的肠道黏膜炎及肾毒性[21,24]。

1.4 调节化疗药物代谢及转运影响化疗药物疗效及不良反应

研究表明,秀丽隐杆线虫中,大肠杆菌核糖核苷酸代谢途径及细菌维生素B6和B9可促使5-Fu代谢为活性产物5-氟尿嘧啶核苷,从而增强5-Fu药效,而降血糖药物二甲双胍可通过抑制细菌的一碳代谢途径降低5-Fu疗效[25-26]。

在药物不良反应方面,肠道菌群产生β-葡萄糖醛酸酶可作用于伊立替康的代谢产物SN-38葡萄糖醛酸苷(SN-38G),使其转化为活性代谢产物7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱(SN-38),导致对肠道上皮细胞的剂量限制性毒性作用[27]。同时肠道菌群可使抗病毒药物索利夫定转化为中间体溴乙烯尿嘧啶,抑制5-Fu降解导致其在血液中蓄积,两药联合使用曾导致15例患者死亡[28]。

相反,肠道中分离的植生拉乌尔菌、肺炎克雷伯菌和大肠杆菌可通过还原脱糖机制促进多柔比星代谢,从而减少多柔比星的毒性[29]。临床试验也表明,肠道假单胞菌中分离纯化的羧肽酶G2可分解代谢和灭活甲氨蝶呤[30],羧肽酶G2现已被美国食品药品监督管理局批准静脉用于血浆甲氨蝶呤浓度大于1 μmol/L且存在排泄延迟或肾功能损害的患者[31]。

2 微生物菌群对分子靶向药物疗效及不良反应的影响

分子靶向药物主要针对恶性肿瘤病理生理发生、发展的关键靶点进行治疗,其中疗效与肠道菌群密切相关的分子靶向药物包括人表皮生长因子受体2(HER2)抑制剂曲妥珠单抗、表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)抑制剂西妥昔单抗及血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)抑制剂贝伐珠单抗。

研究显示,曲妥珠单抗无应答的HER2阳性乳腺癌患者肠道中,毛螺菌科、苏黎世杆菌科、双歧杆菌和普雷沃氏菌呈低丰度。而在HER2阳性小鼠中使用抗生素,可损害曲妥珠单抗诱导的肿瘤中CD4+ T细胞和颗粒酶B阳性细胞招募、树突状细胞(DC)活化和IL-12产生的过程,导致曲妥珠单抗疗效降低[32]。同样,经化疗药物与西妥昔单抗或贝伐珠单抗联合治疗的CRC患者中,肠道菌群的多样性与良好治疗结局相关。而肠道中肺炎克雷伯菌、乳杆菌、双歧杆菌及具核梭杆菌高丰度可能提示该治疗方案下疾病进展的不良结局[33]。

在药物不良反应方面,因接受VEGF抑制剂引起腹泻患者的肠道菌群组成中,拟杆菌丰度较高而普雷沃氏菌及双歧杆菌属分布较少[34]。此外,利妥昔单抗诱导的肠道损伤不良反应可能与肠道菌群失调引发的免疫反应相关,而补充罗伊氏乳杆菌后肠系膜淋巴结中致病性辅助性T细胞(Th)减少,调节性B细胞增加,从而缓解利妥昔单抗引起的胃肠道毒性[35]。

3 微生物菌群对免疫治疗药物疗效及不良反应的影响

Vétizou等[36]及Sivan等[37]首次发现免疫检查点抑制剂(ICIs)的疗效与肠道菌群密切相关,ICIs为阻断肿瘤免疫逃逸通路的单克隆抗体,免疫检查点涉及细胞毒性T淋巴细胞相关抗原4(CTLA-4)、程序性死亡[蛋白]-1(PD-1)及其配体(PD-L1)。其中小鼠肠道脆弱拟杆菌产生多糖激活瘤内DC细胞,在肿瘤引流淋巴结中诱导Th1应答;此外,细菌脂多糖可通过激活肥大细胞招募肿瘤浸润T淋巴细胞,从而增强抗CTLA-4药物疗效[36,38]。而肠道双歧杆菌属通过激活DC刺激CD8+T细胞肿瘤浸润,肠道副干酪乳杆菌也可促进结直肠癌小鼠中CD8+T细胞肿瘤浸润,增强抗PD-L1的疗效[37,39]。

在黑色素瘤患者中,抗PD-1疗效与肠道中嗜黏蛋白阿克曼菌、长双歧杆菌、空肠弯曲杆菌、粪肠球菌和瘤胃球菌科的丰度呈正相关,其中嗜黏蛋白阿克曼菌可诱导DC分泌IL-12参与PD-1阻断治疗[40-42]。而使用抗生素可导致晚期黑色素瘤患者及非小细胞肺癌患者对ICIs的原发耐药性降低,总生存期(OS)和无进展生存期(PFS)缩短[43]。

同时,质子泵抑制剂(PPI)通过影响肠道双歧杆菌和瘤胃球菌科丰度、调节肿瘤微环境pH值及招募M2亚型巨噬细胞等机制导致ICIs药效降低。研究显示,PPI与ICIs联合使用导致肿瘤患者的PFS及OS显著缩短[44]。除肠道菌群外,定植于胃黏膜上皮的幽门螺杆菌也与免疫治疗药物疗效相关。PD-1免疫疗法在幽门螺杆菌血清阳性的非小细胞肺癌患者及进展期胃癌患者中疗效较低,可能由于幽门螺杆菌通过影响DC的交叉呈递从而抑制了抗肿瘤CD8+T细胞的活化[45-46]。

ICIs可提高晚期癌症患者的总生存率,然而由于其激活自身免疫可引起结肠炎等一系列免疫治疗相关不良反应(irAEs),其可能与肠道中厚壁菌门/拟杆菌门水平上升相关[47]。而肠道双歧杆菌通过增加调节性T细胞水平,肠道罗伊氏乳杆菌通过降低3型先天性淋巴细胞水平[48],可缓解ICIs诱导的小鼠结肠炎不良反应[49]。

4 调控微生物菌群改善抗肿瘤药物疗效及不良反应

4.1 抗菌药物调控微生物菌群

抗菌药物指具有抑制或杀灭病原菌能力的化学物质,通过影响肠道菌群与抗肿瘤药物产生相互作用。回顾性临床研究报道,靶向产生胞苷脱氨酶细菌的抗生素可改善胰腺导管腺癌患者对吉西他滨的应答[50]。新霉素与伊立替康联合使用,可降低患者粪便中β-葡萄糖醛酸酶活性及SN-38浓度,缓解腹泻不良反应[51]。然而仍有多项研究表示抗菌药物可诱导肠道菌群失调,导致抗肿瘤药物治疗不良结局[43,52]。因此,抗菌药物与抗肿瘤药物的相互作用机制仍有待进一步研究。

4.2 益生菌、益生元调控微生物菌群

益生菌是有利于肠道的微生物菌群的统称,多项研究表明益生菌制剂可缓解抗肿瘤药物诱导的肠道黏膜炎不良反应。如鼠李糖乳酸杆菌可恢复小鼠肠道厚壁菌门/拟杆菌门丰度比,改善5-Fu和奥沙利铂联合治疗诱导的小鼠肠道黏膜炎[53]。益生菌合剂(短双歧杆菌、嗜酸乳杆菌、干酪乳杆菌、嗜热链球菌)可恢复肠道菌群失调导致的5-羟色胺过量产生,改善顺铂诱导的大鼠黏膜炎[54]。

益生元指促进体内有益菌代谢和增殖的有机物质。研究表明菊粉通过引起记忆CD8+T细胞应答,增强CRC小鼠中抗PD-1治疗疗效[55]。茯苓多糖及低聚果糖可恢复小鼠肠道菌群稳态,改善肠道上皮屏障,降低5-Fu的毒副作用[56-57]。

4.3 粪便微生物群移植调控微生物菌群

粪便微生物群移植(FMT)指将整个粪便微生物群落,包括细菌、病毒、真菌及其代谢物,从健康供体转移至受体[58],具有调节抗肿瘤药物疗效及不良反应的潜在临床价值。FMT可恢复小鼠肠道菌群稳态,改善5-Fu诱导的肠道黏膜炎且不引发菌血症,具有有效性及安全性[59]。临床试验也证实经FMT治疗后,抗PD-1难治性转移性黑色素瘤患者肠道中双歧杆菌及瘤胃球菌科的丰度提高,可改善对抗PD-1的原发耐药性[60-61]。

5 展 望

抗肿瘤药物的耐药性及毒性是目前抗肿瘤治疗失败的原因之一,而微生物菌群与抗肿瘤药物相互作用是提高抗肿瘤药物疗效、减少药物不良反应的潜在靶点。然而目前研究仍存在一定的局限性:(1)微生物菌群对抗肿瘤药物存在双重作用,细菌-免疫-抗肿瘤药物轴机制仍需进一步研究;(2)多数研究仅基于动物模型,然而人与动物的肠道菌群种类、数量以及比例等并不完全一致,需更多临床试验证实微生物菌群与抗肿瘤药物的相互作用;(3)目前研究局限于体内共生细菌与抗肿瘤药物的相互作用,而体内病毒、真菌也可能影响抗肿瘤药物的治疗[62-63]。因此,未来仍需进一步探索体内微生物与抗肿瘤药物的相互作用机制,为肿瘤个体化治疗提供新方向。

参考文献

[1]Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries[J]. CA-Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71: 209-249.

[2]Zhong L, Li Y, Xiong L, et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2021, 6: 201.

[3]Roden DM, McLeod HL, Relling MV, et al. Pharmacogenomics[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394: 521-532.

[4]Jia W, Li H, Zhao L, et al. Gut microbiota: a potential new territory for drug targeting[J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2008, 7: 123-129.

[5]Alexander JL, Wilson ID, Teare J, et al. Gut microbiota modulation of chemotherapy efficacy and toxicity[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017, 14: 356-365.

[6]Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, et al. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment[J]. Science, 2013, 342: 967-970.

[7]Viaud S, Saccheri F, Mignot G, et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide[J]. Science, 2013, 342: 971-976.

[8]Daillère R, Vétizou M, Waldschmitt N, et al. Enterococcus hirae and Barnesiella intestinihominis Facilitate Cyclophosphamide-Induced Therapeutic Immunomodulatory Effects[J]. Immunity, 2016, 45: 931-943.

[9]Li Y, Dong B, Wu W, et al. Metagenomic Analyses Reveal Distinct Gut Microbiota Signature for Predicting the Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Responsiveness in Breast Cancer Patients[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12: 865121.

[10]Yu T, Guo F, Yu Y, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy[J]. Cell, 2017, 170: 548-563.e16.

[11]Zhang S, Yang Y, Weng W, et al. Fusobacterium nucle-atum promotes chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil by upregulation of BIRC3 expression in colorectal cancer[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 38: 14.

[12]Logan RM, Stringer AM, Bowen JM, et al. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in cancer treatment-induced alimentary tract mucositis: pathobiology, animal models and cytotoxic drugs[J]. Cancer Treat Rev, 2007, 33: 448-460.

[13]Bawaneh A, Wilson AS, Levi N, et al. Intestinal Microbiota Influence Doxorubicin Responsiveness in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer[J]. Cancers(Basel), 2022, 14:4849.

[14]Panebianco C, Adamberg K, Jaagura M, et al. Influence of gemcitabine chemotherapy on the microbiota of pancreatic cancer xenografted mice[J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2018, 81: 773-782.

[15]Huang B, Gui M, Ni Z, et al. Chemotherapeutic Drugs Induce Different Gut Microbiota Disorder Pattern and NOD/RIP2/NF-κB Signaling Pathway Activation That Lead to Different Degrees of Intestinal Injury[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2022, 10: e0167722.

[16]Sfanos KS, Markowski MC, Peiffer LB, et al. Compositional differences in gastrointestinal microbiota in prostate cancer patients treated with androgen axis-targeted therapies[J]. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2018, 21: 539-548.

[17]Pernigoni N, Zagato E, Calcinotto A, et al. Commensal bacteria promote endocrine resistance in prostate cancer through androgen biosynthesis[J]. Science, 2021, 374: 216-224.

[18]Clark AR. Anti-inflammatory functions of glucocorticoid-induced genes[J]. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2007, 275: 79-97.

[19]Menezes-Garcia Z, Do Nascimento Arifa RD, Acúrcio L, et al. Colonization by Enterobacteriaceae is crucial for acute inflammatory responses in murine small intestine via regulation of corticosterone production[J]. Gut microbes, 2020, 11: 1531-1546.

[20]Liu H, Wang J, He T, et al. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health?[J]. Adv Nutr, 2018, 9: 21-29.

[21]Panebianco C, Villani A, Pisati F, et al. Butyrate, a postbiotic of intestinal bacteria, affects pancreatic cancer and gemcitabine response in in vitro and in vivo models[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2022, 151: 113163.

[22]Geng HW, Yin FY, Zhang ZF, et al. Butyrate Suppresses Glucose Metabolism of Colorectal Cancer Cells via GPR109a-AKT Signaling Pathway and Enhances Chemotherapy[J]. Front Mol Biosci, 2021, 8: 634874.

[23]He Y, Fu L, Li Y, et al. Gut microbial metabolites facilitate anticancer therapy efficacy by modulating cytotoxic CD8(+) T cell immunity[J]. Cell Metab, 2021, 33: 988-1000.e7.

[24]Hsiao YP, Chen HL, Tsai JN, et al. Administration of Lactobacillus reuteri Combined with Clostridium butyricum Attenuates Cisplatin-Induced Renal Damage by Gut Microbiota Reconstitution, Increasing Butyric Acid Production, and Suppressing Renal Inflammation[J]. Nutrients, 2021, 13:2792.

[25]García-González AP, Ritter AD, Shrestha S, et al. Bacterial Metabolism Affects the C. elegans Response to Cancer Chemotherapeutics[J]. Cell, 2017, 169: 431-441.e8.

[26]Scott TA, Quintaneiro LM, Norvaisas P, et al. Host-Microbe Co-metabolism Dictates Cancer Drug Efficacy in C. elegans[J]. Cell, 2017, 169: 442-456.e18.

[27]Araki E, Ishikawa M, Iigo M, et al. Relationship between development of diarrhea and the concentration of SN-38, an active metabolite of CPT-11, in the intestine and the blood plasma of athymic mice following intraperitoneal administration of CPT-11[J]. Jpn J Cancer Res, 1993, 84: 697-702.

[28]Okuda H, Nishiyama T, Ogura K, et al. Lethal drug interactions of sorivudine, a new antiviral drug, with oral 5-fluorouracil prodrugs[J]. Drug Metab Dispos, 1997, 25: 270-273.

[29]Yan A, Culp E, Perry J, et al. Transformation of the Anticancer Drug Doxorubicin in the Human Gut Microbiome[J]. ACS Infect Dis, 2018, 4: 68-76.

[30]Widemann BC, Schwartz S, Jayaprakash N, et al. Efficacy of glucarpidase (carboxypeptidase g2) in patients with acute kidney injury after high-dose methotrexate therapy[J]. Pharmacotherapy, 2014, 34: 427-439.

[31]BTG International Inc.VORAXAZE9(Glucarpidase)for injection prescribing information[EB/OL].(2012-01-01)[2023-03-01].http://www.accesdate.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/125327lbl.pdf.

[32]Di Modica M, Gargari G, Regondi V, et al. Gut Microbiota Condition the Therapeutic Efficacy of Trastuzumab in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer[J]. Cancer Res, 2021, 81: 2195-2206.

[33]Chen YC, Chuang CH, Miao ZF, et al. Gut microbiota composition in chemotherapy and targeted therapy of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12: 955313.

[34]Pal SK, Li SM, Wu X, et al. Stool Bacteriomic Profiling in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Receiving Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhi-bitors[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2015, 21: 5286-5293.

[35]Zhao B, Zhou B, Dong C, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri Alleviates Gastrointestinal Toxicity of Rituximab by Regulating the Proinflammatory T Cells in vivo[J]. Front Microbiol, 2021, 12: 645500.

[36]Vétizou M, Pitt JM, Daillère R, et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota[J]. Science, 2015, 350: 1079-1084.

[37]Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, et al. Commensal Bifido-bacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy[J]. Science, 2015, 350: 1084-1089.

[38]Kaesler S, Wölbing F, Kempf WE, et al. Targeting tumor-resident mast cells for effective anti-melanoma immune responses.[J]. JCI insight, 2019, 4: 125057.

[39]Zhang SL, Han B, Mao YQ, et al. Lacticaseibacillus paracasei sh2020 induced antitumor immunity and synergized with anti-programmed cell death 1 to reduce tumor burden in mice.[J]. Gut microbes, 2022, 14: 2046246.

[40]Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors.[J]. Science, 2018, 359: 91-97.

[41]Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients[J]. Science, 2018, 359: 97-103.

[42]Matson V, Fessler J, Bao R, et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients[J]. Science, 2018, 359: 104-108.

[43]Hamada K, Yoshimura K, Hirasawa Y, et al. Antibiotic Usage Reduced Overall Survival by over 70% in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Patients on Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy[J]. Anticancer Res, 2021, 41: 4985-4993.

[44]Giordan Q, Salleron J, Vallance C, et al. Impact of Antibiotics and Proton Pump Inhibitors on Efficacy and Tolerance of Anti-PD-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 716317.

[45]Oster P, Vaillant L, Riva E, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection has a detrimental impact on the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies[J]. Gut, 2022, 71: 457-466.

[46]Che H, Xiong Q, Ma J, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with survival outcomes in advanced gastric cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors[J]. BMC cancer, 2022, 22: 904.

[47]Chaput N, Lepage P, Coutzac C, et al. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab[J]. Ann Oncol, 2017, 28: 1368-1379.

[48]Wang T, Zheng N, Luo Q, et al. Probiotics Lactobacillus reuteri Abrogates Immune Checkpoint Blockade-Associated Colitis by Inhibiting Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 1235.

[49]Wang F, Yin Q, Chen L, et al. Bifidobacterium can mitigate intestinal immunopathology in the context of CTLA-4 blockade[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018, 115: 157-161.

[50]Imai H, Saijo K, Komine K, et al. Antibiotic therapy augments the efficacy of gemcitabine-containing regimens for advanced cancer: a retrospective study[J]. Cancer Manag Res, 2019, 11: 7953-7965.

[51]Alimonti A, Satta F, Pavese I, et al. Prevention of irinotecan plus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin-induced diarrhoea by oral administration of neomycin plus bacitracin in first-line treatment of advanced colorectal cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2003, 14: 805-806.

[52]Kuczma MP, Ding ZC, Li T, et al. The impact of antibiotic usage on the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy is contingent on the source of tumor-reactive T cells[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8: 111931-111942.

[53]Chang CW, Liu CY, Lee HC, et al. Lactobacillus casei Variety rhamnosus Probiotic Preventively Attenuates 5-Fluorouracil/Oxaliplatin-Induced Intestinal Injury in a Syngeneic Colorectal Cancer Model[J]. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 983.

[54]Wu Y, Wu J, Lin Z, et al. Administration of a Probiotic Mixture Ameliorates Cisplatin-Induced Mucositis and Pica by Regulating 5-HT in Rats[J]. J Immunol Res, 2021, 2021: 9321196.

[55]Han K, Nam J, Xu J, et al. Generation of systemic antitumour immunity via the in situ modulation of the gut microbiome by an orally administered inulin gel[J]. Nat Biomed Eng, 2021, 5: 1377-1388.

[56]Yin L, Huang G, Khan I, et al. Poria cocos polysaccharides exert prebiotic function to attenuate the adverse effects and improve the therapeutic outcome of 5-Fu in Apc(Min/+) mice[J]. Chin Med, 2022, 17: 116.

[57]Andrade MER, Trindade LM, Leocádio PCL, et al. Association of Fructo-oligosaccharides and Arginine Improves Severity of Mucositis and Modulate the Intestinal Microbiota[J]. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins, 2023,15:424-440.

[58]Borody TJ, Khoruts A. Fecal microbiota transplantation and emerging applications[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011, 9: 88-96.

[59]Chang CW, Lee HC, Li LH, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Prevents Intestinal Injury, Upregulation of Toll-Like Receptors, and 5-Fluorouracil/Oxaliplatin-Induced Toxicity in Colorectal Cancer[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21:386.

[60]Davar D, Dzutsev AK, McCulloch JA, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients[J]. Science, 2021, 371: 595-602.

[61]Borgers JSW, Burgers FH, Terveer EM, et al. Conversion of unresponsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibition by fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with metastatic melanoma: study protocol for a randomized phase Ib/IIa trial[J]. BMC cancer, 2022, 22: 1366.

[62]Nakatsu G, Zhou H, Wu WKK, et al. Alterations in Enteric Virome Are Associated With Colorectal Cancer and Survival Outcomes[J]. Gastroenterology, 2018, 155: 529-541.e5.

[63]Coker OO, Nakatsu G, Dai RZ, et al. Enteric fungal microbiota dysbiosis and ecological alterations in colorectal cancer[J]. Gut, 2019, 68: 654-662.

- 搜索

-

- 1000℃李寰:先心病肺动脉高压能根治吗?

- 1000℃除了吃药,骨质疏松还能如何治疗?

- 1000℃抱孩子谁不会呢?保护脊柱的抱孩子姿势了解一下

- 1000℃妇科检查有哪些项目?

- 1000℃妇科检查前应做哪些准备?

- 1000℃女性莫名烦躁—不好惹的黄体期

- 1000℃会影响患者智力的癫痫病

- 1000℃治女性盆腔炎的费用是多少?

- 标签列表

-

- 星座 (702)

- 孩子 (526)

- 恋爱 (505)

- 婴儿车 (390)

- 宝宝 (328)

- 狮子座 (313)

- 金牛座 (313)

- 摩羯座 (302)

- 白羊座 (301)

- 天蝎座 (294)

- 巨蟹座 (289)

- 双子座 (289)

- 处女座 (285)

- 天秤座 (276)

- 双鱼座 (268)

- 婴儿 (265)

- 水瓶座 (260)

- 射手座 (239)

- 不完美妈妈 (173)

- 跳槽那些事儿 (168)

- baby (140)

- 女婴 (132)

- 生肖 (129)

- 女儿 (129)

- 民警 (127)

- 狮子 (105)

- NBA (101)

- 家长 (97)

- 怀孕 (95)

- 儿童 (93)

- 交警 (89)

- 孕妇 (77)

- 儿子 (75)

- Angelababy (74)

- 父母 (74)

- 幼儿园 (73)

- 医院 (69)

- 童车 (66)

- 女子 (60)

- 郑州 (58)